Remembering one of Martin Scorsese’s strangest and most memorable films.

Most of Martin Scorsese’s films have cult followings, but The King of Comedy is one of his few films to gain a massive cult without also gaining classic status among the larger body of film fans. It was Scorsese’s biggest commercial flop when it was first released in February 1983, opening to very divisive reviews, but it now has an avid following, even inspiring the title of one of my favorite film blogs. Interest in the film has further grown since the release of Joker in 2019, with most retrospective reviews focusing on the film’s supposedly renewed “relevance” in the social media age, which to my mind, is one of the most boring and cliched ways of looking at it. Far more interesting is its place in Martin Scorsese’s filmography. It was considered to be something of an anomaly for the director on its original release, but now that Scorsese has further expanded his cinematic portfolio, it’s easier to discern the strong thematic connections between this film and his other work. Moreover, like most of Scorsese’s best films, it is, first and foremost a fascinating character study. Once again, he has Robert De Niro play someone who we’d keep way past arm’s length in real life, yet thanks to both the director and lead actor, becomes a strangely compelling figure.

One of the reasons for the film’s financial failure was that critics and audiences alike initially found the movie quite unpleasant. Not painful to sit through, just uncomfortable. That’s not surprising considering that Robert De Niro’s Rupert Pupkin is one of the most unlikable lead characters in film history, and as had been the case with Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, they only kept watching because De Niro himself is so charismatic and mesmerizing. Inevitable comparisons are always made between Pupkin and De Niro’s Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver because of their loner status and obvious insanity, but there are also key differences. Rupert Pupkin may be somewhat less dangerous and more palatable than Travis Bickle, but that’s only because he lacks the homicidal tendencies and corrosive bigotry that’s at the core of Bickle’s persona. He compensates by taking Travis’s narcissism and sense of entitlement and maximizing these traits to the point where they become downright malignant.

The most repellent aspect of Pupkin’s personality is his complete lack of a work ethic and puffed-up perception of his own dubious talents. His refusal to admit his own fallibility or to actually improve himself makes it impossible for either the audience or the other characters to appreciate his potential. He’s the type of person any teacher or professor is painfully familiar with, the lazy egomaniac who puts no effort into their assignments and then stalks and even threatens the instructor when they don’t get the A+ they think they’re entitled to receive. How badly he compares to Ellen Burstyn in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, who acknowledges she must work hard to attain her dream of being a famous singer. He even looks awful next to Ray Liotta in Goodfellas, whose desire to be a powerful gangster is an even less laudable goal than Rupert’s, but at least he “honestly” works his way up from the bottom ranks! Needless to say, even Travis Bickle almost starts to look good next to him. Bickle may be a repulsive bigot and sick murderer, but at least he acts out of a misplaced altruism and sense of duty that Pupkin can’t even muster.

Yet De Niro’s Rupert Pupkin ultimately bears less a resemblance to his Travis Bickle than to his saxophonist Jimmy Doyle in Scorsese’s New York, New York. Both are frustrated artists/performers who allow their obsessions with success in their chosen field (music for Jimmy, comedy for Rupert) to totally consume their lives. Both crave fame and attention and behave in a childish manner when denied the opportunity to perform in public. Granted, there are two major differences: Doyle is actually (eventually) sympathetic. and he’s also genuinely talented. But he is every bit as immature, pushy, and arrogant, to the point where it’s a struggle to appreciate not just his qualities as a person but his skills as a musician as well. His obsessive courting of Liza Minelli’s singer in the film’s first half mirrors Pupkin’s harassment of Langford, and would be just as creepy if he didn’t also demonstrate his sincere love for her and desire to help her professionally. Jimmy may be basically selfish and egotistical, but he does let the caring and selfless side he has repressed shine through by the end. He may have been a cad, but at least he has grown up over the course of the film.

Pupkin, on the other hand, only thinks about himself. Exclusively. And he never grows up. We never once believe he genuinely loves bartender Rita (Diahnne Abbott as the only truly sympathetic character in the entire film), even when he fantasizes about marrying her on live TV. It’s clear he only regards her as a means to fulfill his selfish dreams, and the fact that she almost completely disappears from the movie when Pupkin’s attempt at breaking into Langford’s house fails (and she sincerely apologizes to Jerry) only confirms this fact. He enlists the aid of fellow unstable Langford fan Masha not out of a desire to mutually help one another but because he sees her as another pawn in his schemes (it’s also evident that Masha is trying to use Pupkin as well). People are literally just figures on the TV screen, pictures on the wall or cardboard cutouts to him; he’s totally incapable of putting himself in the shoes of another person. It’s not that he lacks the imagination to do so; far from it, as we can see from his elaborate fantasies being staged onscreen. It’s just that he’s so selfish, all his imagination goes toward self-flattery.

So much has been written about the contributions of Scorsese, De Niro and even Jerry Lewis to the film’s success that other important contributing figures have been neglected. Screenwriter Paul D. Zimmerman (a former writer for Sesame Street!) is one of them; so much of the dialogue bears the obvious improvisational imprint typical of Scorsese and De Niro’s collaborations that the importance of Zimmerman in coming up with the story and characters is unfairly forgotten. Comedienne and cult figure Sandra Bernhard as Masha, Pupkin’s even more deranged complice en crime, is also strangely often overlooked. Like the film itself, Bernhard is a decidedly acquired taste. I’ve never known quite what to think of her, appreciating her quirkiness and wit yet at the same time disliking her all-too-frequent nastiness and vulgarity. It was only after stumbling upon her show Reel Wild Cinema on YouTube that I found myself thoroughly enjoying her, even finding her quite lovable. And it was only after watching King of Comedy that I really appreciated her brand of humor, as there’s a strong continuity between this film and Bernhard’s later routines. Bernhard goes one step further in her own critiques of celebrity culture, mocking the audience itself for its obsession with fame for fame’s sake. Her concert film Without You I’m Nothing amplifies this message so loudly that while watching it, you may feel like Langford yourself, bound up in cellophane while she rants and screams in your face. With her fiery shock of curly red hair, accusing eyes and cruel mouth cradled by ruby-red lips, Bernhard’s Masha is rather reminiscent of the mad Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) in one of Scorsese’s favorite films, Black Narcissus, albeit louder and shriller.

Scorsese has conceded in his 1988 Criterion laserdisc commentary for Black Narcissus that the influence of director Michael Powell, while evident in virtually all of his films, was especially important on King of Comedy. From The Red Shoes to Peeping Tom, Powell dealt with characters trapped between reality and fantasy (sometimes literally, as in Stairway to Heaven), tottering between actuality and delusion, often ending in tragedy for all concerned. Scorsese has dealt with similar characters and themes throughout his career, and they’ve become more prominent in his work, as The Aviator, Shutter Island and Hugo all ably demonstrate. Yet it’s most evident in King of Comedy, where Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker brilliantly transition between the “real” world and Pupkin’s fantasy land. Moreover, this particular thematic obsession provides continuity between not just this film and Taxi Driver but his subsequent After Hours, possibly the strangest film he has ever made. All three movies form a Nightmarish New York trilogy where the largest American city serves as a map for the character’s psyches (and in the first two films, psychosis as well).

Scorsese takes visual cues from Powell as well to help reinforce the importance of these themes to an understanding of the main character. Rupert Pupkin lives in the real New York in exterior shots, one that’s familiar from other Scorsese films. Once the film moves to interior shots, especially scenes at Pupkin’s home or at Langford’s studio, the movie shifts to a surreal world of bright lights, deep shadows and vivid colors, all visual trademarks of Powell’s work, even when the action has not shifted directly into Rupert’s fantasies. Much of the credit for the film’s unusual yet effective look goes to production designer Boris Leven, who had previously created the deliberately artificial Manhattan in New York, New York. His work here is oddly reminiscent of his previous set designs for two science fiction classics, Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain and William Cameron Menzies’s Invaders From Mars, and it’s probably not a coincidence in the latter case. Menzies’s film was deliberately structured as a literal child’s nightmare, and Leven’s bizarre sets reflected these artistic intentions. Rupert Pupkin may be a grown man, but he also lives in a similarly childish fantasy world, and once again, Leven was able to fulfill the director’s vision with a set design emphasizing amorphous shapes and reflective surfaces that perfectly expresses the main character’s solipsism and paranoia. Considering that Scorsese himself has cited Invaders From Mars as a personal favorite, it would not be surprising to learn that he specifically asked Leven to go back to those old designs for inspiration.

Another reason the film may have received such a chilly reception upon its initial release is that on a first watch, the viewer may find it as difficult to distinguish between these transitional scenes of fantasy and reality as it evidently is for Pupkin himself. As would be the case with the similarly-themed Fight Club sixteen years later, the cult for the film quickly grew as home video allowed viewers to rewind and look and listen carefully for any clues or nuances they may have missed with their first viewing. For instance, there’s a key fantasy scene where Pupkin is imagining that he’s in Langford’s office, who is congratulating him on the “brilliant” demo tape he sent him. Because of the way Schoonmaker immediately cut from De Niro waiting in the lobby in the “real” world to sitting in Jerry’s office, I at first did not grasp immediately that this was supposed to be a fantasy sequence. Only after the scene ends and immediately cuts to Langford exiting the building in a brown jacket (he wore a navy blue one in Pupkin’s daydream) that it became clear to me. On my second viewing, it became immediately obvious since Leven’s set design for this scene consists of mirrors everywhere, reflecting the actors at every angle. This is precisely the sort of place a narcissist like Pupkin would imagine himself being in!

I’ve also appreciated the movie more after my third and fourth viewings and even found myself being entertained more with each subsequent watch. At the same time, the film remains flawed to me, not deeply so, but I still can’t quite rank it at the same level as such near-perfect Scorsese films as Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Goodfellas. Other than the surprisingly superb Jerry Lewis, I also have problems with the performances from the main cast. Sandra Bernhard, as mentioned before, is not always on the right side of annoying, and Diahnne Abbott isn’t given enough time to really develop her character. I even have a few quibbles with Robert De Niro’s performance, as great as it often is. Oftentimes there’s the sense that he’s sometimes a bit too mannered and calculated (as with the cue cards scene), when he’s at his best when he’s as unpredictable as his character. I also remain unsatisfied with the abrupt ending and its too-obvious attempt at indicting the audience in perpetuating the delusions of celebrity culture. Even after several viewings, it remains confusing if this concluding montage is supposed to represent reality, Pupkin’s fantasy, or both. Such ambiguity worked beautifully in the endings for Taxi Driver and The Last Temptation of Christ, but not so much this time.

Still, even his flawed films ably demonstrate why Scorsese is one of the best and most argued-about of directors. The King of Comedy may not be Scorsese’s finest film, but it remains one of his most fascinating. It has taken me and many others multiple viewings to fully appreciate it, and although I obviously still can’t say that I’m completely satisfied with it, I at least understand now why it has such a strong cult following. Let’s hear it for Martin Scorsese, ladies and gentlemen, Martin Scorsese.

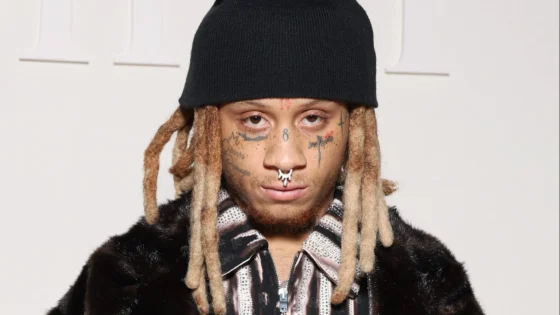

Image: IMDB/20th Century Fox