“Last summer, trying to find a picture to see, I went to the two multiplexes in Beverly Hills,” Robert Altman said, in Peter Biskind’s 1998 book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. “There wasn’t one picture that an intelligent person could say, ‘Oh, I want to see this.’ It’s just become one big amusement park. It’s the death of film.”

Even before that, it was very clear that Altman wasn’t too happy with the state of Hollywood. A leading light of the New Hollywood movement of the ’70s, Altman directed classics like M*A*S*H, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, California Split, and Nashville, all between 1970 and 1975.

But by the dawn of the Reagan era, as the New Hollywood collapsed amid the rise of Jaws and Star Wars, Altman became disillusioned, and also fell somewhat out of favor. That quote in Biskind’s book was far from the only time Altman assailed the Hollywood studios and what he felt had done to the movies.

Then, in 1992, when he was 67 years old, Altman arrived with a comeback movie that torched Hollywood, allowing the director to settle some scores while bringing much of Hollywood along for the ride. The movie was The Player, which was a huge success, influenced years of similar satires for years to come, and it returned its director to prominence. Altman would continue to work regularly, making acclaimed films all the way up until his death in 2006.

The Player was adapted from the novel by Michael Tolkin, who also wrote the screenplay. More than anything else, it’s the work of a filmmaker who has something very specific that he wants to say, executes that message with perfection, and manages to be a hugely entertaining movie at the same time.

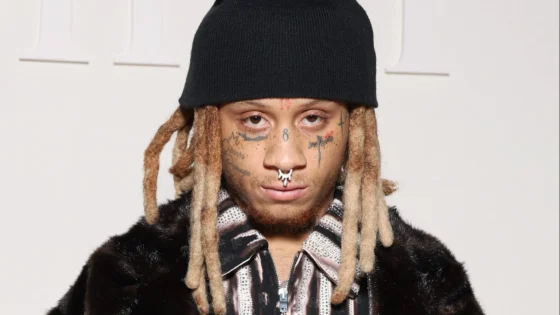

Tim Robbins — just 32 years old at the time — stars in the film as Griffin Mill, an executive at a Hollywood studio, who’s specifically known for being writer-friendly, and for finding promising scripts from unheralded writers.

He’s put upon, though, both because an upstart rival (Peter Gallagher) is on the verge of taking his job, and because he’s getting threatening postcards that he thinks are from a writer he blew off. Griffin ends up meeting a guy who he thinks is the writer (Vincent D’Onofrio) and, after a confrontation, kills him. The movie then turns into Crime and Punishment, as guilt over the killing brings his stress level to unimaginable highs.

Aside from the main plot, The Player is inundated with Hollywood insider patois.

The movie’s famous opening scene, featuring an unbroken take lasting over seven minutes, introduces this milieu, and for the rest of the movie, every other scene seemingly has people pitching, speculating, or discussing ideas for movies. And while The Player was very much a bitter denunciation of Hollywood by a disgruntled outsider, it brought along all the insiders- the film features a seemingly endless series of star cameos, from Burt Reynolds to Cher to Andie MacDowell to Malcolm McDowell. The “regular” cast also featured Whoopi Goldberg, Fred Ward, and Greta Scaachi.

The plot congeals around a movie pitch for an earnest movie about the death penalty, one that’s to have no stars and feature an unhappy ending- clearly, meant to represent the challenging films of the ’70s that Altman made (and appreciated.) The Player‘s ending shows how that searing movie ended up after a run through the studio meat grinder: It now stars Bruce Willis and Julia Roberts and ends with a dramatic rescue and one-liner. (Robbins, humorously, would direct a death penalty movie three years later, Dead Man Walking, and while it had stars, it much more resembled the pitch from The Player than where the movie ended up.)

The Player got positive reviews and three well-deserved Oscar nominations, for directing, writing, and editing, although it won none. But Altman’s career was rejuvenated, and his follow-up, 1993’s Short Cuts, was one of the director’s better films. The last four films of his career, Dr. T and the Women, Gosford Park, The Company, and A Prairie Home Companion, were all outstanding.

Three decades on, a couple of things are fascinating about The Player. One is that it spawned many other satires about showbiz, and most of them were terrible. Few of them got why The Player worked and had its satirical bite. Only Get Shorty, five years later, compares, but even that came at things with a completely different angle. Most recently, Judd Apatow’s The Bubble was almost the worst possible version of this sort of film, one that tried to satirize both showbiz and the COVID pandemic without having anything, in the slightest, to say about either one.

It’s also notable that the Hollywood of The Player is practically unrecognizable today. The studios, to the point where they still exist, aren’t getting a lot of their movie ideas from the out-of-left-field musings of unknown screenwriters. Established intellectual property roles the roost and has for quite some time, and Hollywood is further away than ever from Robert Altman’s idealized 1970s.

Watch The Player