10 Great Films about Addiction

We chose ten of our favourite films about substance and alcohol abuse.

The Panic in Needle Park

Written by Joan Dion and John Gregory Dunne; based on the book by James Mills

Directed by Jerry Schatzberg

USA, 1971

Al Pacino gives a riveting performance as Bobby, an energetic street hustler and heroin addict who forms a bizarre yet accepting relationship with a homeless woman, Helen, played by Kitty Winn. The Panic in Needle Park is a gut-wrenching expose to the drug culture in New York City. American films of the late sixties, such as Easy Rider, Performance, and The Trip, portrayed the edgy glamour and counter-culture boom of the sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll revolution, but after the release of The Panic in Needle Park, filmmakers forecast the downward spiral of addiction. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll transgressed into heroin, prostitution, and jail. To this day, no other film has topped the realistic portrayal of the drug culture. Shot in a documentary-like fashion, the camera feels distant and cold, peering into the lives of IV drug users as they inject heroin, scene after scene. The images of cooking and drawing up dope are very detailed; the director uses a series of close-up shots, which convey the ritualistic nature of shooting up heroin. There is no glamour, no exuberance, only the unflinching reality of addiction. What’s most compelling about this film is the sincerity between the two leads, and it’s a relationship that sets the template for other addiction-fueled romance yarns, such as Candy, Drugstore Cowboy, and the ever-powerful, Leaving Las Vegas.

Shame

Written by Steve McQueen and Abi Morgan

Directed by Steve McQueen

UK, 2011

Filmmaker Steve McQueen (no relation to the deceased actor) helms a thought-provoking and sad portrait about a successful business executive, Ben (Michael Fassbender), who’s a sex addict constantly on the prowl. When Sissy (Carey Mulligan), Ben’s sister, barges into his life, he finds it difficult to maintain his sexual routine. Actor Michael Fassbender bares all – full-frontal nudity and implosive anguish – as his character tries to mask his sexual exploits while keeping up a stable appearance in a chic, upper-class Manhattan society. There is no exposition, no character back-story, only a solitary man spiraling, along with his co-dependent sister, into bleak and utter sadness. Steve McQueen is one of the few filmmakers who can evoke a visceral impact utilizing a minimalistic style – uninterrupted long shots and tracking movements – rather than dialogue exchange or heavy cutting. The audience immerses into Ben’s troubling existence. Many scenes show Ben masturbating, surfing pornographic websites, and for the most voyeuristic moment in the film, quietly observing a couple having sex against a window. One of the most powerful scenes in the film is where Ben watches Sissy sing “New York, New York” in a restaurant, and the camera cuts between close-up shots of their faces. Tears suddenly stream from Ben’s eyes, and the audience senses a traumatic experience from their past. The vagueness of this cinematic moment leaves room for discussion, which makes the scene all the more arresting. Whether sex, heroin, or alcohol—it doesn’t matter what the drug is—the obsessive nature of the addict is painstakingly captured.

Requiem for a Dream

Written by Hubert Selby Jr. and Darren Aronofsky, based on the novel by Hubert Selby Jr.

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

USA, 2000

Requiem for a Dream is one of the most forceful cautionary tales about addiction ever made and has gained a huge cult following among young viewers. Filmmaker Darren Aronofsky takes the hip-hop, frenzied style he employed in his black-and-white début, Pi, and injects it with steroids. The film contains punctuated sound effects, montages, split-screen effects, and fast and slow-motion effects—the style has a pulse of its own and doesn’t let up until the last image. The narrative follows the lives of junkies as they spiral into one nightmare after another. Jennifer Connelly and Jared Leto play as lovers on heroin, hoping to keep up their dreams of success and independence without falling into the expected trappings of addiction: prostitution, jail, and bodily harm. Veteran actress Ellen Burstyn steals the show as a widowed mother who gets hooked on speed with hopes to fit into her favorite red dress for a faux television scam. Ironically, she does slim down enough to wear the red dress, but the occasion isn’t for the fanciful dream of television, but the horrid reality of being committed into an insane asylum. Requiem for a Dream is one of the most shocking films about addiction. The haunting soundtrack, alone, will linger long after the screening. Dreams do come true.

Brain Damage

Directed by Frank Henelotter

Written by Frank Henelotter

USA, 1988

Brain Damage is a terrific horror-comedy about a young man possessed by a talking parasite named Aylmer who injects him with a psychedelic drug in exchange for human brains. Filmmaker Frank Henelotter made his claim to underground fame with the minuscule budget Basket Case, which has all the trappings of an exploitation horror film (tons of gore and nudity), but the storyline of a man seeking revenge on the doctors who separated him and his deformed Siamese twin has as much psychological insight as Brian De Palma’s Sisters. Brain Damage is a unique parable of heroin addiction, and the film has charming stop-motion effects, side-splitting humor, and enough stylized blood to cover a mural. Apart from the horror and comedic elements, Brain Damage exposes the sleazy atmosphere of New York City in the 80′s, including porn theaters, punk-rock clubs, scrap yards, and roach-infested motels. Brain Damage is a manic, over-the-top achievement that demands multiple viewings.

Leaving Las Vegas

Written by Mike Figgis; based on the novel by John O’Brien

Directed by Mike Figgis

USA, 1995

Nicholas Cage won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal as a dire alcoholic on a personal quest to kill himself. Cage plays Ben Sanderson, a failed screenwriter who moves to Las Vegas and forms a unique bond with Sera (Elizabeth Shue), a hooker who accepts his last exit. The film is one of the most emotionally involving and darkest love stories ever told a story about acceptance and a sincere glimpse into the final stages of alcoholism. Mike Figgis shot the film on 16mm, tarnishing the glitz and glamour of “sin city.” The style is so raw and uncompromising that the director uses the sound of a helicopter propeller to underscore the helicopter shots of Las Vegas. The scenes of Sera talking to an unseen therapist give the narrative a docudrama feel; it gives her character a psychological arch and reasoning towards her commitment to Ben. Nicolas Cage’s physical features—pale skin, thinning hair, bags under his eyes—are just as compelling as his drunken rants and raves. Cage’s performance evokes the alcoholic tendencies of Ray Milland’s character in the Billy Wilder classic, The Lost Weekend, which is also about a failed writer on the brink of self-destruction.

The Lost Weekend

Written by Charles Bracket; based on the novel by Charles R. Jackson

Directed by Billy Wilder

USA, 1945

Billy Wilder’s award-winning classic still holds up with today’s standard of edgy, addiction-related films, and the old black-and-white imagery cast an almost hallucinatory spell over the viewer’s senses. Ray Milland plays Don Birnam, an alcoholic writer who, after staying dry for ten days, goes on a weekend bender. Billy Wilder captures the sordid itch of an alcoholic, such as the scene where it cuts to Don’s point of view and zooms in to an extreme close-up into his shot glass. In one memorable flashback, where Don watches an opera in which all the characters are drinking champagne, the shot dissolves into a row of empty raincoats, and the camera tracks forward to a pocket that reveals a superimposed image of a whiskey bottle. The distinct editing effects put us inside the head of the alcoholic, a subjective perspective that rounds the character. The Lost Weekend builds to a delirious and horrific conclusion in which Don hallucinates rodents, and it’s just as terrifying as when Tippie Hedren was attacked in Hitchcock’s The Birds.

Jungle Fever

Written by Spike Lee

Directed by Spike Lee

USA, 1991

Although the central theme deals with interracial relationships and crossing new boundaries, the subplot about Samuel L. Jackson’s crack-addicted character, Gator, is the most compelling. Spike Lee isn’t a director who believes in making films about one idea; many ideas and themes lurk at the surface of his work. In Jungle Fever, Lee brought the crack-cocaine epidemic to the forefront. Samuel L. Jackson gives an all-out, grotesquely humorous performance, and his transformation into a homeless junkie is so vibrant, sad, and real. Spike Lee is known to exaggerate certain situations, such as when Wesley Snipes ventures into the “Taj Mahal”—the Playboy Mansion of seedy crack-houses—and the massive amounts of crack smoke swarms the air like a 1930s monster movie. The stylized atmosphere differentiates Lee’s work from other directors. Jungle Fever isn’t his best film (Do the Right Thing is), but it’s still an evocative provocation.

Drugstore Cowboy

Written by Gus Van Sant and Daniel Yost; based on the novel by James Fogle

Directed by Gus Van Sant

USA, 1989

Matt Dillion and Kelly Lynch portray lovers on the road who lead a group of misfit junkies as they rob pharmacies and hospitals. Director Gus Van Sant expresses not only the self-destruction but the quirky behaviors that go with addiction, such as Matt Dillon’s superstition of leaving a hat on a bed. Drugstore Cowboy is an excellent drama about characters who don’t know where they’re going but certainly know how they want to feel. Gus Van Sant isn’t afraid to depict the humor and pathos of a junkie’s road journey. For instance, in the scene where Dillon shoots up in the car, the camera focuses on the backseat window and a superimposed image of a spoon, syringe, a cow, a tree, and then a farmhouse drift into the background, which conveys a whirlwind of euphoric thoughts. The scene is a clever wink at the tornado sequence in The Wizard of Oz. Drugstore Cowboy is a highly original film, both in story and style.

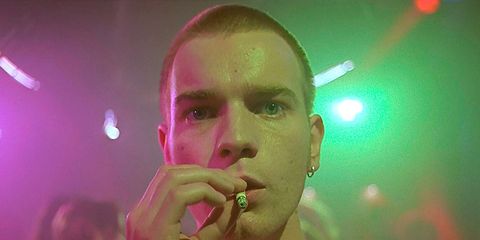

Trainspotting

Written by John Hodge; based on the novel by Irvine Welsh

Directed by Danny Boyle

UK, 1996

Trainspotting is a vivacious, dark comedy about young Mark Renton, played by Ewan McGregor, and his struggle with heroin addiction and turbulent friendships among the scum of Scotland. Trainspotting became a zealous undertaking in the drug genre, and the film doesn’t condone drug abuse but doesn’t relish in the destructive turmoil either. Director Danny Boyle has a lot of fun with his canvas, employing cool camera tricks, freeze frames, extreme POV shots, and the best of British pop music. Boyle’s ultra-hip style expresses the effects of both heroin injection and heroin withdrawal. The writer and director portray these bottom-of-the-barrel characters as if they were rock stars, and when we’re on drugs, don’t we always feel like rock stars?

Permanent Midnight

Written by David Veloz; based on the book by Jerry Stahl

Directed by David Veloz

USA, 1998

Permanent Midnight is a drug film that sort of slipped under the radar upon its release, and it’s by far Ben Stiller’s best and most daring performance. Stiller portrays TV writer Jerry Stahl, and shows his descent into full-blown heroin addiction. Permanent Midnight is an ugly vision of addiction, and while Stahl hobnobs with show-biz executives, he’s just as inclined to mingle with dope dealers and addicts. His character is a walking contradiction; for example, he uses heroin first thing in the morning but still makes time to jog five miles, keeping up with LA trends. Although the film would’ve benefited from a more straightforward structure, rather than told in flashbacks, it’s unafraid to show the icky lifestyle of a junkie.