Gobsmackingly brilliant; Gummo marks the directorial debut of Kids writer and indie rebel Harmony Korine (Spring Breakers, Trash Humpers). Upon its initial release, Gummo drew critical fire and Korine was denounced as an exploitative brat with a movie camera. But what emerges from his twisted mind is a stylish, poetic, and brutally honest portrait of an American underclass whose misery is rarely addressed on the big screen. Korine arranges a total deterioration of narrative logic and social norms, and Gummo seems to be provocatively anti-everything: everything but life. Gummo is cruel, bitter, and sometimes offensive but also occasionally quite moving. For example, The infamous scene in which Solomon shoots the listless grandmother in the foot while his buddy disconnects her life support, could be read as an act of mercy. Gummo is full of despair, yet populated by an optimistic ensemble: “Life is beautiful,” says Tummler. “Without it, you’d be dead.”

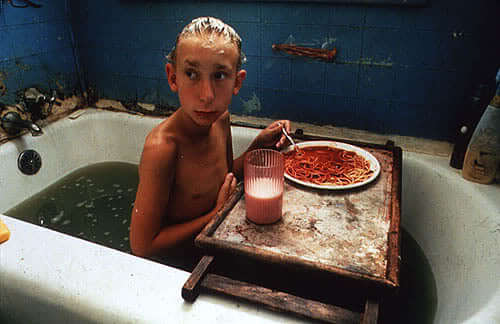

On April 3, 1974, a tornado ripped through the small southern town of Xenia, Ohio, nearly wiping it off the map. Twenty-three years later and the inhabitants of Xenia haven’t fully recovered. What unfolds is the strange daily activities of a group of misfits and a set of vignettes that amounts to a full-out freak show. In the first scene, Bunny Boy (Jacob Sewell) stands on a freeway overpass and pisses on the traffic below while wearing his pink rabbit ears. What follows is a scene that will make most audiences walk out. Needless to say, cat lovers should be warned – as kittens fall victim to drowning, poisoning and pellet guns. There’s a mentally handicap girl who shaves her eyebrows and confesses that she breastfeeds her doll, all after she’s pimped out by who might be her older brother – and that famous shot of Jacob Reynolds eating spaghetti in a tub full of dirty bathwater is something you’ll never forget. The movie is a collage of troubling, elusive images. Kids huff glue, a dwarf is sexually harassed, a gossip columnist/pedophile lures young women into his car, and a group of trailer park boys wrestle with furniture. And it gets worse. Chloë Sevigny prances around with taped nipples to Buddy Holly’s “Every day,” and Linda Manz tap-dances while her son (Jacob Reynolds) lifts makeshift dumbbells (made out of cutlery), to the strains of Madonna’s “Like a Prayer.” There is also a great deal of dark humour, and according to Korine, only seventy-five percent of the film is scripted. Gummo concludes with the sounds of Roy Orbison fading into a chorus of “Yes, Jesus Loves Me,” forcing us to confront our prejudices and feel… something.

For all its unsettling imagery, there’s also some compassion in Gummo.

Korine isn’t interested in the narrative, and he doesn’t believe a film should follow any specific guidelines. Gummo does not feature a well-packaged plot but instead a series of fascinating vignettes that form a mosaic of the small town. Korine breaks all the rules of traditional filmmaking, interspersing impressionistic and documentary-style sequences with voice-over narration, various film stocks, memoirs, and monologues, and sometimes within the same scene. Shot in about twenty days, with a budget of $1.3 million, Korine displays great command of rhythm and pace. Working with cinematographer Jean-Yves Escoffier (Good Will Hunting), the first time director sustains a depressive mood via sound and image. The film is plagued with muted colors and lit with fluorescent lights which give the movie a grimy, yellowish tint – and in between scenes of these characters acting out their strange routines, is an eclectic mix of tunes, ranging from black metal to Gospel hymns. Out of 40 speaking parts, only five were played by experienced actors and despite having top billing in the opening credits, Linda Manz only appears approximately 43 minutes in. Additionally, she is onscreen for roughly five minutes. Jacob Reynolds (Solomon) was 13. Nick Sutton (Tummler) was 17. Jacob Sewell (Bunny Boy) was 14. And Darby Dougherty, who plays the youngest of the three sisters, was only 10. Korine’s knack for casting and talent for directing his actors go hand in hand – and his refusal to condemn or condescend, anyone, saves the film from exploitative voyeurism. What another director would work with an actor who stabbed him on set?

For all its unsettling imagery, there’s also some compassion in Gummo. In a famous interview, Herzog asked, “Who do you want the audience for Gummo to be?”

Korine answered, “I never thought about that while I was making it, but I feel it’s definitely most important if young people see it because it’s a new kind of film with a new kind of syntax. Younger people have a different kind of sensibility, and I think they’ll understand it. But if someone said that I was the voice of my generation, I couldn’t agree with that. I’m just the voice of Harmony”.

Indeed he is. Gummo is troubling but undeniably a one-of-a-kind. It was my favourite film of 1997, and to this day, it still abounds with strange beauty.

– Ricky D