When thinking of a conventional graphic novel, silence isn’t always considered as a defining characteristic of the all-time greats. Sure, the absence of action can work effectively as a breather between big action set pieces, but rarely is silence essential in moving the narrative forward. Most climaxes involve fists flying and earth-shattering revelations coming to light.

Writer Jeff Lemire is exemplary in bucking this trend. While he has enjoyed incredible success with more traditional superhero comic storylines such as Green Lantern, Teen Titans, and Old Man Logan, Lemire’s Essex County, Sweet Tooth, and Black Hammer stand shoulders above his other works. Black Hammer is an entire universe of its own, spawned from Lemire’s deconstruction of typical superhero motifs and clichés, while Essex County and his other story are deeply personal and human dealing with abandonment, broken families, and even modern life in Native American communities. It is in stories such as Essex County and Roughneck that allow Jeff Lemire to use silence as a tool to convey the intense emotion and sentiment in each respective story.

Essex County is a collection of several interlocking stories written by Jeff Lemire that take place in the real-life Essex County, Ontario. While each of the three stories is beautifully rendered and written, the longest story and the most gut-wrenching is the middle story, “Ghost Stories”. “Ghost Stories,” tells the life of ex-hockey pro named Lou Lebeuf through his own distorted perspective. Lou is reliving his past decisions that ruined his life and his relationship with his brother Vince. What makes his tale even more heartbreaking is that he is a spectator to it. Lou is clearly suffering from Alzheimer’s or some dissociative mental illness because he seemingly stumbles into his past, unaware of whether it is the present or not.

Lou’s one moment of clarity is the night he slept with Vince’s wife Beth, in which there are no speech or sound bubbles. Instead, Lou’s older face is imprinted on the moon, helpless as he watches his greatest mistake. There’s no prolonged “Nooo!” or needless exposition placed above it, the scene speaks for itself and the silence is essential in conveying the heartbreak and remorse felt by Lou.

Perhaps what makes this scene most effective is that it takes place after perhaps the rowdiest part of the book. In the scene prior, Lou’s hockey team is drinking to celebrate a win, and there is simply a lot of speech everywhere on the page. It’s almost overwhelming compared to the relative scarcity of dialogue throughout the rest of the story. Most of the time there is at least Old Lou’s expositional narrative over the scene, but in the moon scene, there is nothing. This scene is perhaps the best in the entire collection due to its composition and placement, and the silence is essential in its construction.

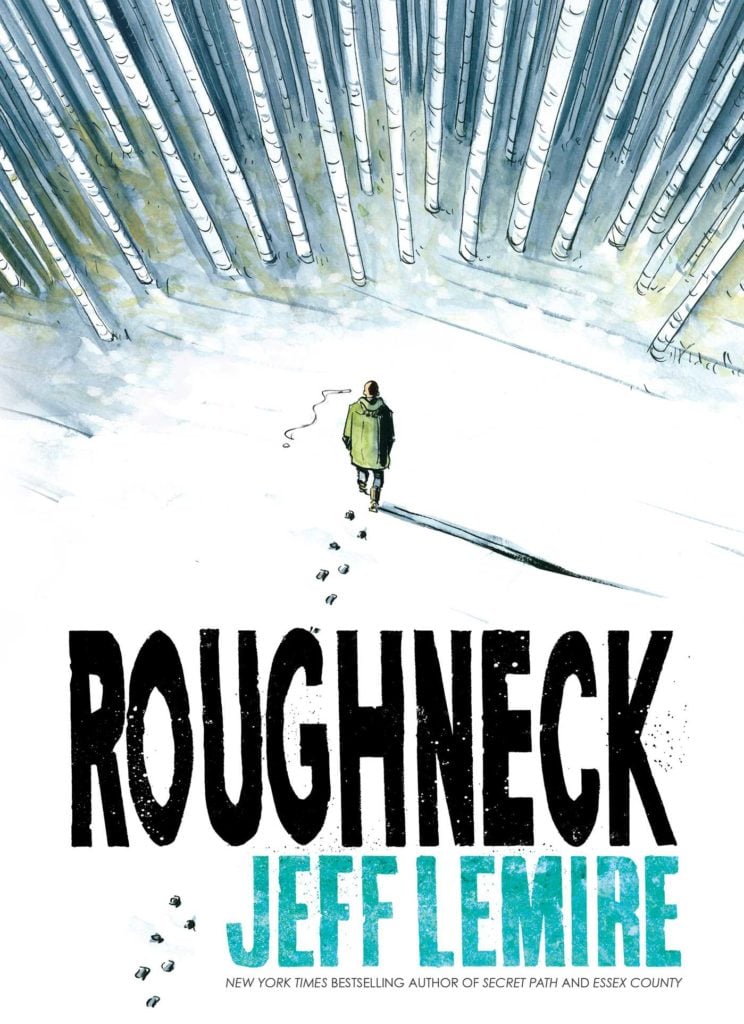

“Roughneck” is a more streamlined story focused around ex-pro hockey player (a recurring motif in most Lemire stories) Derek Ouelette who brutes his way through life beating anyone who taunts him within an inch of their lives. Once Derek’s younger sister re-enters his life, he must take her out to the woods to help her detox and escape her abusive ex. This entire story is punctuated with spurts of silence followed by abrupt scenes of graphic violence. While Lemire uses more color in this story than in all of Essex County, I hesitate to call this story colorful. Most of the scenes are draped with a deep watercolor blue, which adds a dullness and somber feel to the scenes. But when things get violent, the sporadic red used is glaring almost distracting.

Two scenes in which silence and color work harmoniously in this story are when Derek and Al kill the deer, and the deer’s past flows out of the beast in color and when Derek falls to Beth’s ex Wade, and Derek’s past flows out of him in color similarly. The color and silence work in tandem with each other to imbue the scenes with a sense of spirituality. The only other word on the page in which Derek falls is a ‘Thud!” and it’s almost unnoticeable. The reader’s eyes are drawn to the past as it escapes Derek. Narration over these scenes would take away from the spirituality of their passing. Narration would cheapen the emotion.

Jeff Lemire isn’t the only or first writer in graphic novels to use silence as a plot device or as a way to convey deep emotion. But few writers have as firm of a grasp on it as Lemire.

- Ben Snyder